Good Will Hunting was recently on TV and as I watched Will's childhood gang go bar-hopping and street-fighting I was reminded of the masculine ability to form intimate tribes between the ages of 17 and 25. Towards the end of the movie Chuckie (Ben Affleck) confesses to Will (Matt Damon) that he hopes one day Will won't answer the door when he comes to pick him up because he has used his knowledge to get out of south Boston. Through most of the movie Will rejects opportunities at love and work guarding himself and staying safe with his gang. At the end of the movie Will finally leaves his tribe for both love and career. I can in many ways relate to leaving my tribe at around this age. My hunch is that men become increasingly lonely after the age of 25. There may be a period from 25 to 30 where we are absorbed enough in pursuits not to notice it too much but it eventually surfaces. Are the sorts of relationships portrayed in this movie only applicable to a certain stage of life? Does our culture of romantic love and powerful career sever these relationships unnecessarily? Anyway, I miss my old tribe. And in case you forgot, here is a great scene.

Sunday, August 31, 2008

Good Will Hunting on Relationships

Posted by

Unknown

at

10:19 p.m.

0

comments

![]()

Saturday, August 30, 2008

Apologetics vs Criticism

Given the comments on the following quote over at Faith and Theology there is little remaining doubt that apologetics continues to be the ready target of high-brow theological discourse. Here is the quote,

“The philosopher is not an apologist; apologetic concern, as Karl Barth (the one living theologian of unquestionable genius) has rightly insisted, is the death of serious theologizing, and I would add, equally of serious work in the philosophy of religion.”I should state that I am not assuming a monolithic approach to apologetics. I consider apologetics an attempt at stating the positive case for a held truth. So this of course can be done in many different forms. I think apologetics is often criticised for its reactivity and inappropriate methodology. The methodology piece is again of course dependent on the particular expression. My question is what the difference is between apologetics and the type of criticism entered into readily by so many of the bloggers who so roundly denounce apologetics? Both assume that the reality of error and the possibilty of at least expressing things more truthfully (I am not thinking of things propositionally here). I would have to say that good apologetics at least has the benefit of being courageous enough to put out substantive contributions. I would see Halden's (Inhabitatio Dei) ongoing work around martyology and non-violence as a type of apologetic project. I agree that we do not need to defend our faith or submit entirely to modern material-scientific methodolgy, but again I see that as a type of apologetics.

—Donald M. MacKinnon, The Borderlands of Theology: An Inaugural Lecture (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1961), 28.

Anyway, I always start to get a little cautious when academia finds too clear a target for criticism as opposed to entering critically (and/or constructively) with particular discourses.

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:20 p.m.

0

comments

![]()

Friday, August 29, 2008

Who Wrote the Bible - Part III - The Tormented Historian

Having laid the mystery of J and E to rest F. moves on to outlining the next time period significant for the Bible, 722-587 BC. After the fall of Israel Judah shifted significantly in its political and religious outlook. Politically they functioned from a considerable position of weakness in the world, religiously they were now an integrated people without real tribal boundaries as refugees from the north would have fled south.

Having laid the mystery of J and E to rest F. moves on to outlining the next time period significant for the Bible, 722-587 BC. After the fall of Israel Judah shifted significantly in its political and religious outlook. Politically they functioned from a considerable position of weakness in the world, religiously they were now an integrated people without real tribal boundaries as refugees from the north would have fled south.

King Hezekiah ruled Israel from about 715 to 687. In that time Hezekiah introduced political and religious reforms rebelling against Assyria and centralizing worship to the Temple in Jerusalem. After a number of ‘bad’ kings Josiah became king at the age of 8 (2 Kgs 22) and ruled from 640 to 609. Josiah also carried out religious reforms re-centralizing Temple worship. It is also during Josiah’s reign that we read about the high priest Hilkiah having found a “book of the law.” After Josiah’s reign Israel quickly goes downhill with a few ‘bad’ kings before being exiled by Babylon in 587.

F. states that the book found by Hilkiah was Deuteronomy (D). One of the main arguments for this that both Deuteronomy and Josiah are concerned with the centralizing worship. This is in contrast to the worship of Saul, Samuel and David who worshiped at various sites. F. also recognizes the literary relationship between Deuteronomy and Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, and 1 and 2 Kings (the Deuteronomistic History; DH). In addition covenant becomes a central theme particularly as it leads up to the Davidic covenant which promises the line of David the throne eternally. The question then is why the writer would so emphasize the covenant knowing that the throne of David does not endure. F. suggests that there were two versions of DH. It is claimed that the first version was written to culminate in King Josiah. Inordinate space is given to describe Josiah’s reign, Josiah is referred to by name in prophecy against Jeroboam in 1 Kgs 13 (and it is Josiah who explicitly destroys the alter in Beth-El which Jeroboam established). The author of DH evaluates all the kings and includes some criticism even for the good ones (David and Hezekiah) but in reference to Josiah these words are spoken, “Neither before nor after Josiah was there a king like him who turned to the LORD as he did—with all his heart and with all his soul and with all his strength, in accordance with all the Law of Moses. . . . nor did any like him arise after him” (interesting side note the NIV does not include that final line, even though it is clearly attested in the MT not even as a textual variant) This leads F. to further compare how Moses is compared to Josiah in DH. The phrase “nor did any like him arise” is used only in reference to Moses (Deut 34:10) and Josiah. Josiah is the only one known to have fulfilled Moses command to love God with all your heart, soul, and strength. The Book of Torah is mentioned only in Deuteronomy and Joshua and then in reference to Josiah. Both figures grind idols “thin as dust.” F. includes other similarities between the two sources. Josiah was meant to be the end and culmination of history. But after Josiah the two main themes of DH disappear, the Davidic covenant and centralized worship.

In attempting to discern the author of these books F. looks to levitical priest but discards the Temple priest because they are Aaronids and distinguish themselves from other Levites and D does not make such distinction. D also never refers to an ark, cherubs, or other Temple instruments. F. points again to the priests at Shiloh as the possible authors of Deuteronomy. F. is more specific saying that the law code of Deuteronomy was likely written by these priests. It was the author of DH that took this law code (that Josiah found) and added the narrative of Moses’ final days around it, as well as the later history.

F. goes on to connect the prophet Jeremiah to the writing of DH. Jeremiah is linked to Josiah’s reign. Jeremiah has close connection to son’s of the priest and scribes who bring Josiah the book of the law. Jeremiah is the only prophet connected in his writings to Shiloh (which he calls the place where God’s name will dwell; Jer 7:12). Jeremiah is also a priest from Anathoth where Abiathar was originally banished by Solomon. Jeremiah is also the son of Hilkiah, though F. is quick to point out that this may not be the same Hilkiah that found the scroll. More pressing is that fact that it has been observed that the language of Jeremiah and Deuteronomy are similar. Jeremiah then wrote the history of the people until the culmination of Josiah. But what of the remaining kings that ruled until exile? F. likens the case to writing a history of John F. Kennedy before he was assassinated. F. maintains that allusions to exile and idolatry were then added throughout DH. Jeremiah also rewrote the consequences of Manasseh, Josiah’s grandfather. Manasseh’s rule was so bad that it irrevocably caused the destruction of Judah beyond what Josiah’s reforms could accomplish (2 Kgs 23:26). F. then says that Jeremiah re-worked the covenant to show that the Mosaic covenant with the people was first and so the eternal unconditional throne of David would be irrelevant if there were no people to rule. This reworking was done by Jeremiah in exile. F. ends his chapter on D by characterizing Jeremiah as a man tortured by truth unable to leave either accounts alone. The hope of Josiah remains but the judgment of idolatry cannot be avoided.

Posted by

Unknown

at

7:38 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Who Wrote the Bible - Part II - This Post Brought to You by the Letters J and E

J and E exist largely in the first four books of the Bible (though significantly less in Leviticus and Numbers). The names of course derive from the way each source refers to God J/Yahweh and Elohim.

F. is quick to point out that the differences go far beyond the name used for God. F. identifies J with Judah (the south) and E with Israel (the north) demonstrating the connection that the sources have with each geographic location. For instance in the birth narratives of the twelve tribes Elohim is used in reference to the ten tribes while Yahweh is used in reference to the south (Gen 29:32-30:24a; of course 24b has Yahweh, but I am sure he explains that in the article he references :)). F. goes on to look at the Golden Calf story in Exodus (Ex 32) as a definitive case for understanding the E source. With respect to the Levitical priests in Shiloh and their relationship to Moses he states here simply that they “therefore possibly descended from Moses.” This is important because of the way it elevates Moses in the story of the Golden Calf and implicates Aaron. This story then is also a stab at the golden calves set up by Jeroboam when he established his own religious system apart from these priests (see last post). This criticism of Jeroboam in this story (where the singular golden calf made by Aaron is referred to in the plural) is further strengthened by its connection to Jeroboam’s explicit statement regarding the golden calves he established. He says to the people, “Here are your gods, O Israel, who brought you out of Egypt” (1 Kgs 12:28 cf. Aaron Ex 32:4, 8). It is then the Levites who come to the rescue at the bequest of Moses. Joshua is also saved from implication because he is a northern hero coming from the tribe of Ephraim. In this account then E in addition to attaching the south is also attacking the religious system of the north while still keeping his hope in it.

If E associates with Moses then the Numbers 12 story of God reprimanding Aaron for criticizing Moses also fits. On the other hand J accounts often have the people complaining to Moses. F. also points out the Ark and its political significance for David and Solomon is never mentioned in E while the Tabernacle and its association with Shiloh is never mentioned in J. The J creation account also has the Garden of Eden protected by Cherubim which would have been important for Judah and not Israel. Again in the Exodus account J has God saving the people while in the E account Moses is the one sent (Ex 3:8, 10).

With respect to their commonalities F. is clear that he believes the two writers produced versions. They were “drawing upon a common treasury of history and tradition because Israel and Judah had once been one united people.” With the Assyrian exile of Israel a number of refugees from the north would have flooded south and brought with them their texts. Instead of rejecting one version F. holds that the newly combined people of the south would not have allowed one story to be told without the other and so both aspects of the versions were combined. Combining the two then averts the tension between which one would have been viewed as authoritative.

Posted by

Unknown

at

12:32 p.m.

1 comments

![]()

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Halden on Donald

Good post over at Inhabitatio Dei. A couple of quotes,

“Evangelical identity, at least in the U.S. is so utterly determined by the American political imagination and the capitalist economy which grounds it, that it is unable to express or realize itself except through the political-economic architecture of America, regardless of what political subdivision it finds itself in.”

“For Christian politics to be truly Christian they must be, at their very core, nonreactive. The peace of the city of God is in no way determined, constituted, or defined by the agonism of the earthly city.”

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:33 p.m.

0

comments

![]()

Who Wrote the Bible - Part I - The World that Produced the Bible - 1200-722

In terms of interpretive approach to the Bible I believe largely in a literary ‘canonical’ approach. However, in terms of understanding the formation of the Bible (or the Old Testament in particular) I find Richard Elliott Friedman’s account fascinating and in many of the general claims convincing. I thought it would be helpful for my own clarity to work through in detail the claims he makes in Who Wrote the Bible. Whether you accept the Documentary Hypothesis or not this account opens the vistas of the historical context in which the Bible existed.

F. begins with the rise of the Davidic and Solomonic monarchies. Key in this description is the movement from the worship and sacrifice in

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:43 p.m.

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, August 24, 2008

The Only Offensive

From this morning's sermon,

It has often been noted that the armour described [in Ephesians 6] is not meant for offensive attack. There is no spear, bow, or long sword. The equipment described assumes close and intimate contact. It is interesting that the only piece of equipment used for any sort of offence is the sword of the Spirit which is the word of God. We often make truth or righteousness or even salvation as the sword we wield. We try to outdo our opponents in disputes over truth. We claim victory in our acts of righteousness. Or we divide people over our claims about salvation. Instead of offensive weapons Paul describes these things as gifted to us, that we take up and dress ourselves in. This sword of the Spirit is also mentioned in the book of Hebrews where it says, “For the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart. Nothing in all creation is hidden from God's sight. Everything is uncovered and laid bare before the eyes of him to whom we must give account.”

And so even this one offensive object is something we ourselves can never master or control but is something that we allow to work on ourselves as much as others. When we allow the sword of the Spirit, the word of God, free movement it shifts from being the crusaders sword to the surgeon’s scalpel and the priest’s sacrificial knife able to make cuts and incisions that work for healing and wholeness.

Posted by

Unknown

at

8:51 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: nonviolence, peace, sermon, violence

Thursday, August 21, 2008

The Bible in Three Easy Steps

Now feel free to criticize these categories but I thought they were a place to start. What I am hoping to do move the context away from a purely apologtic 'defence' of the Bible. I am not sure if perhaps I should begin with a bit of epistemology and distinguish the relationship between modern science and Bible. I will likely also focus on canon and community (looking at least a little at James Sanders) recognizing emphatically the many (and mostly unknown) hands that were a part of leading to their flasy youth devotional Bible. I think testimony is important recognizing the ongoing communication that surrounding (and was included within) the Bible's formation. In any event I hope to elevate the human end of the Bible while still recoginizing it is as revelation. I hope to post more as this unfolds. The problem is always getting started with youth. I need something zany don't I . . .

Posted by

Unknown

at

3:34 p.m.

2

comments

![]()

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

Imagine

Last Sunday's sermon on Jubilee

Posted by

Unknown

at

11:14 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: political theology, politics, sermon, social concern

Tuesday, August 12, 2008

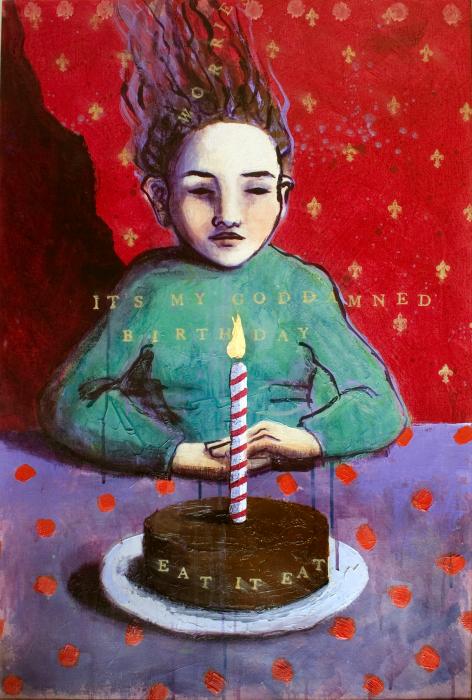

The Year was 2002 . . .

The year was 2002. Pink's Get this Party Started could be heard blasting from car radios, the first Euros were printed in Europe, the US congress authorized the President to use force in Iraq and the first post on IndieFaith forum was submitted.

The year was 2002. Pink's Get this Party Started could be heard blasting from car radios, the first Euros were printed in Europe, the US congress authorized the President to use force in Iraq and the first post on IndieFaith forum was submitted.

August marks the birthday for IndieFaith though the site itself has earlier unknown origins. For those of you who have felt some distaste over the name IndieFaith I will let you into its history. I was originally experimenting with Angelfire's free websites and when you registered your domain name it always began with www.angelife.com the there were some choices for a /directory after which you added your /name. 'indie' was on of the few intelligable subdirectories to choose from and so www.angelfire.com/indie/faith was born. The name itself has always left me feeling a little uneasy. Indie can strike me as too pretentious or too individualistic. Though on the other hand it can also garner feelings of marginal authenticity. I am happy to remain a little uneasy with my title. Here was my original post in IndieFaith Forum,

Theology of presence Theology of covenant, Tomaato, Tomahto. This is a quote from A Homily on Acts 2 “To have faith in the Bible is to believe its promises and to believe in its record of God's work in the life of human history. The Bible then becomes a whole. We see the promise to Abraham, the Exodus out of Egypt, deliverance of the Promised Land, the death and resurrection of Jesus, and the giving of the Holy Spirit to the Acts Church. However, these spectacular events are accompanied by the wandering in the desert, the exile, the destruction of the Temple. For whatever the reason God appears to break into history at different times with varying degrees of force. The Bible gives us no reason to think that, outside of God's own timing, does the present Church body need to perform in the same manner as the Acts Church. If anything the Bible illustrates how consistently we have misunderstood how it is that God will act and fulfill his will. It is impossible to reduce God's Spirit to a formula and so we must ask what it is that God desires of us.” This then is not a theology of presence, but to shift away from the academic, a theology of the present. In light of covenant promises and accounts God’s presence in the past, how is that God speaks to today. For this dilemma I offer another quote, “Theologian Gustavo Gutierrez extends Hegal's notion of philosophy into theology and says that theology rises only at sundown.” We cannot expect a Christian theology unless we commit to working our “days” amidst the brokenness of our world, and then seriously reflecting on that at the end of the day. I walk around my neighbourhood and I see hookers, dried puddles of blood, domestic disputes, and kids with knives. However, I also hear the sound of hammers, children laughing, and gardens being planted. Move past a theology that binds itself by well-seeming borders and opens itself to engage with those it purports to redeem.

Birthday wishes and monetary donations are welcome.

Posted by

Unknown

at

7:02 p.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: reflections, social concern, theology

Monday, August 11, 2008

Confession; Or Mixed Martial Artist as Hebrew Scholar

On occasion we run across blog entries that give us a glimpse of the all-too ordinary lives of the bloggers. The bloggers begin with some shame in their confession wondering if the few readers they have could possibly respect them after such a confession. Perhaps it is professor of sociology admitting they watch (and are addicted to) American's Next Top Model or an admitted film snob confessing his guilty pleasures. Well anyway, here goes.

I grew up enjoying wrestling. I had two older sisters and so I never got many chances to wrestle growing up and so I watched the WWF or bush league AWA and wrestled with pillows in my basement. Now, fortunately, over time I drifted away from the wrestling entertainment business and in 1993 I came across something else. I am not sure if I heard about first or simply saw the VHS cover in a small corner store in my town that rented videos. It was called the Ultimate Fighting Championship.  And for four seasons I watched fighters with backgrounds as diverse as boxing to Samoan Bone Crushing come together to test their skills. And for four seasons (except one due to dehydration) I watched the 165 pounder Royce Gracie beat them all.

And for four seasons I watched fighters with backgrounds as diverse as boxing to Samoan Bone Crushing come together to test their skills. And for four seasons (except one due to dehydration) I watched the 165 pounder Royce Gracie beat them all.

In retrospect I see something actually quite beautiful in that convergence. It was a truly interdisciplinary step (though it was of course admitted that it favoured some). I lost track of UFC for years until this year. In our recent move we now get some channels that play some UFC matches. Things have changed. There are now time limits and rounds and they stand up the opponents if there is not enough 'action'. The shift has moved away from free-style and is geared now towards a more 'exciting' fight. Plus nearly everyone is now trained in the style Gracie introduced.

This being said I started seeing previews for UFC 87 and got swept up by the hype. The day after the pay-per-view event I scoured the internet looking for highlights. I found my body tensed through each round and my emotions shifting from exhilaration to fear and concern. I witnessed respect and sportsmanship (among most). And heard the stories of those who left Wall Street to fight or how grew up homeless and found this as a way out. And highly anticipated the main event for the night the welterweight champion (and Canadian) George St. Pierre vs the scarper Jon Fitch (if you really want to you can see the fight here).

So anyway, what can I say I really enjoyed the fights. I do not translate this directly into a popular masculine spirituality. How do I justify or understand this expression? To be honest I am not sure. I actually find these matches more respectful than most other sports. In other sports there is always the temptation to 'cheat' in order to gain an advantage. In the UFC I believe the only rules are no biting, eye gauging, punches to the back of the head and groin shots (though they wear cups) and I have never seen someone try to use these things to there advantage. I don't think these guys are saints, but I do think the nature of the sport allows for more 'honest' competition.

I suspect at bottom the allure of these competitions is the basic desire to be King of the Castle to be capable of some expression in which we are able to control our environment. In this way I can relate my interest in mixed martial arts to my interest in Hebrew in college and philosophical theology now. In college I held firmly that the Bible was the final authority on truth and practice and so in order to best control the play of interpretations I studied the biblical languages. In this way I could use this authority to legitimize or undermine interpretations (and thus control the playing field). This gave way to the study of hermeneutics and its role in philosophy. I began to think that there were philosophical assumptions that guided my interpretations and so I needed to master that field in order to remain in control. Our actions are almost always in the service of stability.

. . . Wait! This is supposed to be a confession! Only guilt and shame, no excuses! Anyone else? The pastor is in . . .

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:05 a.m.

2

comments

![]()

Labels: culture, reflections

Sunday, August 10, 2008

Kroeker on Our War

In "Is a Messianic Ethic Possible?" Travis Kroeker looks at Jacob Taubes and John Howard Yoder's public and social nature of love of the enemy as opposed to Carl Schmitt's private conception. Kroeker quotes this statement by Schmitt,

Never in the thousand-year struggle between Christians and Moslems did it occur to a Christian to surrender rather than defend Europe out of love toward the Saracens or Turks. The enemy in the political sense need not be hated personally, and in the private sphere only does it make sense to love one’s enemy, i.e. one’s adversary

Before disagreeing with the substance of Schmitt's statement Kroeker notes that Schmitt is actually in historical error on the case of Christians and Moslems. Here he quotes the moving piece by Michael Sattler the sixteenth century monk turned Anabaptist a movement of Christians at times condemned to death for not fighting against the Turks,

If the Turk comes, he should not be resisted, for it stands written: thou shalt not kill. We should not defend ourselves against the Turks or our other persecutors, but with fervent prayer should implore God that He might be our defense and our resistance. As to me saying that if waging war were proper I would rather take the field against the so-called Christians who persecute, take captive, and kill true Christians, than against the Turks, this was for the following reason: the Turk is a genuine Turk and knows nothing of the Christian faith. He is a Turk according to the flesh. But you claim to be Christians, boast of Christ, and still persecute the faithful witnesses of Christ. Thus you are Turks according to the Spirit

There were indeed Christians who thought of surrendering rather than forcing surrender. Kroeker then states the type of 'war' this conception of the messianic advocates,

This messianic pacifism is therefore no liberal strategy of depoliticization through the individualization and privatization of the public realm. It is nothing less than a declaration of war, a war of messianic sovereignty over against all other political sovereignties (whether ancient or modern, religio-cosmological or secularist) that order human relations on non-messianic terms. But it is a war waged by martyrs who do not resist their enemies through violence, but witness to another way, the messianic path of enemy-love. Such a politics, of course, will have no moral grounds for boasting in its own strength or virtue or purity. Messianic sovereignty dispossesses the faithful, as is indicated in the hos me logic of I Corinthians 7:29–31:

I mean . . . the time (kairos) has become contracted; in what remains (to loipon) let those who have wives live as if they did not (hos me) have them, and those who mourn as if not (hos me) mourning, and those who rejoice as if not (hos me) rejoicing, and those who buy as if not (hos me) possessing, and those who use the world as if not (hos me) fully using it. For the outward form of the world (to schema tou kosmou) is passing away.

There is a particular kind of “making use” of the world that treats it in a manner appropriate to its ontology of “passing away”—a using that is not proprietary, not related to human sovereignty or juridical ownership, that dwells in the world (“remain in the calling in which you have been called” [7:20, 17]) in a manner that opens it up to being made new, to “being known by God” (I Cor. 8:3).

And further,

The identity of the “Christian” born by the Messianic community, in other words, is not a new universalism that somehow transcends or escapes particularity and difference. Indeed it is not to be related to a form of universal “knowing” of any sort (“if anyone imagines that he knows something, he does not yet know as he ought to know”). It is rather an identity “in Messiah” that seeks the perfection of love not in the domination or possession of any part, but in the apocalyptic transformation of all partial things to their completion in divine love. This transformation occurs in the messianic body conformed to the “mind of Messiah” that willingly empties itself in order to serve the other, a pattern of radical humility and suffering servanthood. It is a pattern that can only be spiritually discerned, even though it is being enacted in the bodily realm that is “passing away,” and therefore appears as failure.

Posted by

Unknown

at

9:08 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: political theology, yoder

Saturday, August 09, 2008

Kill the Postmodern Story . . . But Let Postmodernism Live

I don't have much issue in speaking of postmodernism as a legitimate cultural/intellectual expression (though D. W. Congdon may disagree). I have a difficulty denying the crisis of stable representation and meaning across disciplines as significant 'shift' of some sorts. What I am coming to suspect is that it may in fact be the postmodern story that is the lie in all this. I can remember about ten years ago sitting in an undergraduate class on the sociology of religion learning about the new postmodern reality with its 'incredulity towards metanarratives' and its fragmenting into local, tribal stories. Since then I have heard that story recounted innumerable times in the service of various church related often 'emergent' projects. It has become the default preface in any attempt of the 'new'.

It seems clear to me now, made increasingly clear through writers like Zizek, that the Story of capitalism only grew stronger and incarnated or birthed or abducted the postmodern story as a mode of infinite market production. As quickly as there was any possible life to the postmodern story it was as quickly enveloped into the market. The Master Signifier of the Market has now been able to hide behind the multiplicity of the many expressions all of which offer no true alternative to the current economic model. The postmodern story it seems to be one initiator in this ongoing production.

Posted by

Unknown

at

10:22 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: culture, modernity, postmodernity, theory

Friday, August 08, 2008

Travis Kroeker on Yoder and Augustine: Common Bread Part 2

As I read between Yoder and Cavanaugh I keep thinking that Yoder is not theological enough and that there is a crucial ontological difference between their two projects. Having read Travis Kroeker's article, "Is a Messianic Ethic Possible: Recent Work By and About John Howard Yoder" (Journal of Religious Ethics, 33: 141-174) I realized that in fact ontology itself is a key difference between the two figures.

Yoder intentionally tries to reinstate a Hebraic-historic approach which he pits against a philosophical-Hellenistic mode which is associated with Constantinianism (the whole articulation of the Gospel in terms of ontology then falls into this camp). What this leads to for Yoder are 'sacraments' that translate fluidly into 'secular' practices (i.e. the breaking of bread is the distribution of economic goods) which he calls 'mediating axioms.' It was at this precise point that I was a little at uneasy with Yoder. In Kroeker's article he compares Yoder to Augustine. Augustine is discarded by Yoder for his Hellenistic influences but Kroeker argues that Augustine is nothing if not an exegete. He then goes on to site an article by Gerald Schlabach who sees Yoder as "an interlocutor in the Augustinian tradition, providing a pacifist ecclesial social ethic in answer to Augustine's definitive question: How are we to seek the peace of the earthly city without eroding loyalty to the heavenly one?" It is here that Kroeker offers an important clarification between Augustine and Yoder. He writes,

While Yoder's elaboration of an ecclesial social ethic specifies more clearly the normative material implications of Augustine's own messianic realism in a creative politics for the pilgrim city that 'uses' well the peace of the earthly city, Augustine's more robust theology of creation prevents Yoder's useful 'mediating axioms' from developing into liberal pragmatic compromises of the voluntarist sort. That is, in Augustine's view, 'mediating axioms' that truly reflect the divine ordering of love and therefore contribute to the ordinata concordia of peaceable earthly communities, must have some kind of 'metaphysical' status beyond the value projections of human wills. Otherwise they would not be 'useful.'

[emphasis mine]

Kroeker remains convinced that Augustine is someone to read Yoder in order to develop his thought. At what point does one betray someone's thought in service of another. To what extent does it matter when we offer the common bread of communion? Was Yoder simply wrong in this area? I will probably be offering a few more excerpts from Kroeker's paper.

Posted by

Unknown

at

8:35 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: augustine, mennonite, political theology, yoder

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Cavanaugh and Yoder and the Possibilty of a Common Bread - Part 1?

Being moved by the work of William Cavanaugh I was quickly brought back to the five walls (I am sure there was some functional reason for this) of my church office at Hillcrest Mennonite Church. I can harbour great admiration for the role of the Eucharist in Cavanaugh's Catholic work but can I have that inform in a significant way how I articulate and practice communion here at my Mennonite church? Having recently returned to the work of John Howard Yoder I was looking for some direction.

What I appreciated about C's work was how he based its beginning and end in a theological account of the abundance of God and its relationship to the kenotic expression of Christ and ultimately of our participation in that relationship. I viewed this in contrast to the recent highly functionalist accounts of responding to our social ills (namely Claiborne and McLaren). Between these two expressions I find of course that Yoder fits in neither.

Yoder does not believe that our strategic response can be in any way adequate to 'fix' the problems around us. Yoder describes what is still an obsessions with contemporary ethics in The Politics of Jesus,

One way to characterize thinking about social ethics in our time is to say that Christians in our age are obsessed with the meaning and direction of history [you could perhaps read here, 'save the planet']. Social ethical concern is moved by a deep desire to make things move in the right direction. Whether a given action is right or not seems to be inseparable from the question of what effects it will cause. Thus part if not all of social concern has to do with looking for the right 'handle' by which one can 'get a hold on' the course of history and move it in the right direction.

Yoder rejects any such handles whether left or right politically as having an inadequate understanding of reality. He states finally that, "It has yet to be demonstrated that history can be moved in the direction in which on claims the duty to cause it to go." Christians are rather to 'look' to the mover of history, Jesus, and walk in step with him.

I thought that at least there was some common ground to work with between Y and C understanding that human ambition and action were insufficient to the challenge before us. However, I think I underestimated the differences in the conception of the Eucharist or Breaking Bread.

Y takes as basic Jesus directions at the Last Supper to be instituting a 'common meal'. In his article "Sacrament as Social Process" Y writes,

What the New Testament is talking about in 'breaking bread' is believers actually sharing with one another their ordinary day-to-day material substance. It is not the case, as far as understanding the New Testament accounts is concerned, that, in an act of 'institution' or symbol making, God or the church would have said 'let bread stand for daily substance.' It is not even merely that, in many settings, as any cultural historian would have told us, eating together already stands for values or hospitality and community formation, these values being distinguishable from the signs that refer to them. It is that bread is daily sustenance. Bread eaten together is economic sharing. Not merely symbolically but in actual fact it extends to a wider circle economic solidarity that normally is obtained in the family.

Y looks to the immediate reality of the practices themselves and takes from that their meaning. Taking aim at a particular Catholic theology whose primary concern is understanding that what is being partaken is the body of Jesus. Y then makes the claim "that there is no direct path from this point to economics. The Roman Catholic authors who establish such a connection have to start over again from somewhere else." In the footnote to his quotation Y cites several Catholic theologians who have made this connection, which he sees as having started 'somewhere else.' This is the question I need to put C. But for now I will ask a brief question of Y.

Y states that the sacramental practices of the church are "wholly human, empirically accessible. . . . Yet each is, according to apostolic writers, an act of God. God does not merely authorize or command them. God is doing them in, with, and under human practice: 'What you bind on earth is bound in heaven.'" As such these practices are fully accessible to the 'secular' public for implementation. Then it follows that "sharing bread is a paradigm, not only for soup kitchens and hospitality houses, but also for social security and negative income tax." This find takes us far from C's almost ontological claims regarding the nature of the Eucharist. And should not Y in some way acknowledge this ontological reality. If the 'sharing bread' is sufficient as a paradigm and if God acts within it then must there not also be a claim to abundance not unlike the feeding of five thousand and the later outlandish claim for the people to feed on Jesus's flesh as outlined in John's gospel? Do we not then come into contact with something more explosive and generative then basic material distribution? Does Y imply something about the material order that he is not letting on here? He states later that these practices were not "revealed from above" but were derived from existing cultural models. I find it difficult to understand these practices as cultural 'all the way down'.

These probes and questions are preliminary as I will need to read more from both C and Y. Any thoughts?

Posted by

Unknown

at

8:10 a.m.

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cavanaugh, liturgy, political theology, yoder

Friday, August 01, 2008

Being Consumed - A Review

William T. Cavanaugh’s Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire is an excellent example of why the church needs theologians, good theologians. While Christian authors are turning increasingly to social and economic issues few are able to blend accessible language with substantial theological content. Many of the current authors addressing these issues articulate the demands of the Gospel in functional terms. Writers (and readers) look for practical ways to ‘apply’ the Gospel to our context. Most of us though with even a passing interest know what we should be doing to help our situation. We should buy fair trade products, support local economies and agriculture, plant a garden, compost, bike, buy twirlly bulbs, etc. And so much of the work of these authors is lost because their argument led entirely to doing and once we get there we realized we already knew that and so begin to feel frustrated or guilty.

Cavanaugh, while in no way neglecting what we would be doing, takes the theological and economic realities of being and of desire seriously. In the brief 100 pages of this book Cavanaugh addresses the issue of economics and Christian desire in four related areas. He begins first with examining our current economic market system, the so-called free market. Cavanaugh is not concerned with whether this system is good or bad in itself he limits himself to asking the question: When is a market free? The market is classically understood as free when employers, employees and consumers are not coerced in their choices. The system is regulated inherently by the demands of the consumer. The market is then considered free when individuals can pursue what they want without coercion within that system. Cavanaugh states that this view defines freedom negatively and carries no vision of its own telos (goal, end, purpose). In the absence of these things Cavanaugh compares the ‘free’ relationship between consumer and corporation to a poker game where you are free to play but your opponent has already seen your hand and knows your compulsion to play. So while the market is indeed based on our wants and desires and though that can provide some regulations Cavanaugh does not assume that our wants are really what we want. Leaning on the work of St. Augustine Cavanaugh introduces a positive notion of freedom which is not freedom to do anything but the freedom from everything towards God. In fact the current market promises of limitless freedoms turn out in fact to be an illusion and in the end unfreedom, restricting environmental health, fair wages, local diversity, etc. A market is free then to the extent that dignified relationships are nurtured with each other, with the land and its resources and ultimately with God which is the telos of human existence.

The second chapter challenges the notion that much of our trouble comes from greed or our attachment to things. Cavanaugh suggests that the issue is actually a profound sense of detachment. Most of us do not hoard we discard. We move quickly from one act of consumption to another. Our culture emphasizes not acquiring but shopping. We are detached from the site of production which has moved from the home, to factories, to across the ocean. Even much of the work we do is no longer related to the act of production or creation. We are therefore detached from the producers who make the products we purchase. Though we hear some stories of the work conditions of factories overseas we are not intimately connected to the particular conditions of we ourselves buy. Even companies themselves are detached as they contract out the work of production and focus on building the image that they can sell. And finally we are detached from the products themselves. We quickly discard the toy in fast-food kid’s meal that was likely made under questionable conditions overseas. Companies of course support our detachment because if we actually valued something we bought it may be longer before we buy the next version of it. Cavanaugh suggests that we are in fact not too ‘materialistic’ but that we are in fact to perversely ‘spiritual’. We are caught up in image and status so we hope that our purchases will take on a mythic quality, though the material thing itself will never satisfy. Into this cycle of endless consuming Cavanaugh introduces the Eucharist as relationship in which we consume but end up being consumed. Rather than the body of Jesus becoming just another commodity we are the ones consumed into the body of Christ. “Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them. (John 6:56). The body of Christ is the place of abundance and unity. It is this Eucharistic reality that restores us from our detachment and brings us into right relationship.

Chapter three explores the relationship between globalization and local expressions. These expressions are argued to be the different sides of the same coin. With the rise of multinational corporations the globe has become a single marketplace in which the cheapest labor is purchased in throughout which homogenous products are offered. Along side of this we witness the celebration of diversity and multiculturalism. There are increased attempts to preserve local expressions. This however, has simply fed into the global economic model where diversity is understood as a consumer choice as opposed to offering some sort of substantial expression apart from economics. In this model we become a pure consumer, a tourist, where even locations are consumed. It is again the body of Christ and the Eucharist that Cavanaugh evokes to respond to this situation. It is the incarnation of Christ, that is always local and particular, that bridges local expression and universal truth. In consuming the body of Christ in the Eucharist and becoming the body then we too allow ourselves to be consumed. “To consume the Eucharist is an act of anticonsumption, for here to consume is to be consumed, to be taken up into participation in something larger then the self, yet in a way in which the identity of the self is paradoxically secured” (84). Here the local is not overcome by the global but participates in it.

The final chapter names the current market system and the body of Christ as representing two economies. Our current market system is based on the assumption of scarcity. In this market we are formed as beings of endless desire and hunger to consume. We live always with the threat that there will not be enough to meet these hungers. Consumption is also the answer to the threat of scarcity, consume more so that there will be more. There is again a type of perverse theology at work here that hopes for the multiplying of loaves and fishes (93). The economy of the Eucharist is one of abundance. We become part of the sustaining life of God and not only that but we are united intimately with our neighbour. They are no longer an ‘other’ to be addressed but they are a part of our very body. This is the economy of the Kingdom and it is the calling of the church.

This book challenges to revisit the relevance and role of communion in our theology and church practice. In his account it is around this faithful expression from which the abundant economy of God emerges. The question becomes whether our own theology and practice allows the same sort of critique and response. Cavanaugh has offered us a rigorously theological account of contemporary economics. He has responded not with finding out what we can do but in understanding what we are when we enter into the body of Christ. It is perhaps this reality rather than a strategy for action that we must begin to take more seriously. This means having our desires consumed in the abundance of Christ rather than having our desires war with each other to consume what cannot satisfy.

Posted by

Unknown

at

11:08 a.m.

7

comments

![]()

Labels: books, social concern, theology